“Lalli unveils a window” is a sequel to “Lalli’s Window.” When eleven-year-old Lalli loses a leg in a car accident, the impact on the family, especially on Lalli herself, is horrendous. Three years later, Lalli has not only learned to accept her one-leggedness not only as a positive (she names her prosthetic “Medusa”!), but as a way to see the world with greater empathy. However, some preconceived notions remain, especially about the nature of Islam. Encouraged by her wise parents who shrewdly hint that Lalli’s Muslim friend Mariam might have doubts about Hinduism too, Lalli realizes that the roots of violence lie in people, not in religions. And when Mariam needs help in saving her older brother Sharif from being recruited by members of the terrorist group ISIS-K, Lalli and her friends rally around her and help the FBI’s counterterrorist unit in destroying the ISIS-K cell in Tucson, Arizona.

Category Archives: Uncategorized

Yasemin and Nirmala

Yasemin Mahsud-McGinty is a fifteen-year-old Pakistani American living in Elmhurst, Chicago, with her parents Iftikhar Mahsud and Jennifer McGinty, and younger brother Sikander. It is three years since she lost an arm in a car accident when the family was vacationing in the Southern Indian hill station of Udagamandalam.

Yasemin’s maturing body leads to serious self-doubts. When she looks into a mirror, she sees a girl who stands at 5’4” with waist-length straight long black hair. Her deep-set chocolate brown eyes stare back at her rather impudently. Yes, she likes her eyes. Her nose? “Aquiline” is what her paternal granddad calls it; “Roman” is her Abu-jaan’s pronouncement. For younger brother Sikander, it’s a ‘beak.’ She herself thinks of it as ‘hooked,’ which isn’t perhaps that complimentary either. What else? Oh yes, her mouth. Rather full, the upper lip straight. Abu-jaan’s friend once commented on her high cheekbones, saying that they lent an intriguing accent to her face. Intriguing? Her long fingers were once her pride, but now she can’t even paint them properly. Self-pity seems to be the rule of the day.

She resorts to wearing a hijab and loose, long-sleeved shirts to cover up Medusa, the name she has given to her prosthetic arm, predicting that her damaged body (she adopts the term ‘unfinish’d’ from Shakespeare’s The Life and Death of Richard the III) would turn boys into stone, especially her neighbor Jeremy Cohen. She plunges ever more deeply into navel-gazing, until a new student (Nirmala Rao-Sumatzkuku) forces her to reassess her own life.

Nirmala Rao-Sumatzkuku is a fifteen-year-old Native American/South-Asian, the only child of Mahesh Rao and Chu’si Sumatzkuku, and born with Cerebral Palsy. Her stock of tales is infinite: fairy-tales, poems, limericks, even jokes. And one day, on her eleventh birthday, she shows her parents something on her computer: a libretto for a comic opera with the title “My soul for a donut.”

When she looks into a mirror, she is proud of the purple and green highlights that are exactly where she wants them in her short black hair. The shortness of her hair shocks her Hopi grandmother in Tucson - Hopi belief in long hair is tied to the earth and nature. And cutting one’s hair is an outward symbol of sadness at a death in the family. Her less traditional paternal grandmother in Hyderabad, India, approves, which makes her Nirmala’s favorite confidant! Dressing is the most difficult chore of the day. Because she has difficulty raising her arms, the top has snap closures on either shoulder that completely opens up to allow her to slide her arms into the garment without having to lift her arms. She loves the slogan on the front of each of her tops:

“CEREBRAL PALSY SLOWS ME DOWN,

BUT IT AIN’T STOPPIN’ ME!!!”

Her mother has to help her into wrap waist jeans. Her legs are practically non-functional, a sorry excuse for something that was supposed to prop you up. But she has to wear shoes, and Nike’s Flyease sneakers are super comfortable. She whispers every day: Thank you, LeBron James! as she bends down to slip her feet into them. And now comes the part that she loves: makeup. She doesn’t need any help at all with it. A bit of mascara to enhance the amber of her eyes. Her eyes are the best part of her – wide-set, with a slight squint that she deliberately, mischievously exaggerates when people stare at her. The arched row of tiny silver and gold studs in each ear that she never takes off shines from her pointy ears. “Makes me look a little like Dobby!”

Like Yasemin, she despairs of ever attracting a boy. The looks of forced pity, sometimes even disgust, that she catches every time she is outside – in the grocery store, in a movie theater, in the park – she is so tired of them. But when she is home, away from all that rejection, her parents’ unconditional love sometimes stifles her. She has to convince them to let her attend a brick-and-mortar school. Meeting other teens would be a challenge, but a change. And her voice synthesizer might impress them too, might even get the attention – albeit platonic – of Ivan Äkerman, a member of the school’s Model UN class.

Posted in Uncategorized

“Bandilanka’s Forgotten Lives”

- What is a possible logline for the book?

How does one even begin to describe the lives of those who have experienced injustice or loss? Each story in this collection empowers them by giving them a voice that can finally be heard. - A short synopsis of the book?

“Bandilanka’s Forgotten Lives” challenges unquestioned assumptions about the validity of tradition and custom. Each story highlights the inherent worth and dignity of the lives of those disenfranchised by these socially-constructed divides. - Location?

The main locale for the stories is Bandilanka, a fictional village in the Indian state of Andhra Pradesh. Other settings are Mumbai, the US (Tucson, AZ, and Charleston, SC), and Canada (Toronto). - Period?

All the stories are set in the 21st century (between 2015 and 2020).

Flashbacks:

a. “An immigrant’s black hole” follows the life of the protagonist from his early childhood until his immigration to the US in 2020.

b. “A washerman’s dream” includes the main character’s recollection of his marriage in the 1950s.

c. “Widowhood across generations” – the story “The fate of a child widow” begins in the year 2007 when the child bride is just 5 years old. It ends in 2020 when she graduates from a college in Toronto, Canada.

d. “The matter of trans lives” mentions the mother’s recollection of her son as a child in 1975 when she realizes that her seven-year-old is trans. Soon afterwards, he is missing from home. Rumor has it that Hijras have taken him. 2020 shows how he re-enters her life as a Hijra. - Detailed synopsis?

“An immigrant’s black hole”: When coal miner Shaikh Idrisi dies of black lung disease, his courageous widow Fatima does not allow her children to land in a mining shaft. With money from her husband’s generous employer, Fatima buys an electric sewing machine and moves with her family to Bandilanka. Eldest son Shah Nawaz soon excels in school, and graduates from the prestigious Delhi School of Economics. He receives a job offer from a company in Charleston, South Carolina. On arrival in Charleston late at night and wearing traditional Shalwar-Kameez, he walks to a nearby pub, and is shot to death because, as a newspaper report announces, his outer wear is “worn by many Al Qaeda terrorists.”

“A cleaning woman’s tale” describes how a rich woman in Bandilanka overworks and treats with contempt her cleaning woman Raasamma. Raasamma tolerates this never-ending abuse for the sake of her impoverished family. However, when the mistress’s lewd brother tries to rape her, Raasamma’s husband and other members of her community take justice into their own hands: they cut off his penis and stab him to death. Next to the dead man lies a figurine of the village goddess Nookalamma whom Raasamma worships as her personal protector.

“A washerman’s dream” gives voice to the recollections of a washerman. After a lifetime of rejection by those who believed that cloth-washing was a process of spiritual pollution, he remembers with his dying breath all the positive moments that have given him the strength to continue: the occasional customer who cares about his increasing ill-health, his wedding as a young boy, a loving wife, adoring and loyal children, and his trusty bullocks Suri and Shiva.

“Tradition’s stranglehold” focuses on how the younger generation in Bandilanka has begun to defend the LGBTQ+ community. Madhu, the daughter of a middle-class family in Bandilanka, is in a committed relationship with Barbara, a German-American woman. However, Madhu’s hide-bound parents try to arrange her marriage to the son of another equally conservative family in Bandilanka. The story ends when Madhu discovers that the potential bridegroom is also gay, and they decide to jointly confront their parents with their choices.

“Familial slaves” tells the story of a ruthless restaurant owner of Indian origin who tempts his gullible nephew Ramalingam in Bandilanka with the promise of work in the US. However, when Ramalingam arrives in the US, the uncle takes away his passport and phone. Ramalingam realizes too late that he is being forced into slave labor and the sex trafficking of young girls. Resistance ends with a fatal stab in his back.

“Nightsoil removes Kaavanna and Kondamma”: Kaavanna, his wife Kondamma, and their children remove night soil from the railway tracks before trains arrive. Before they can finish, Kaavanna collapses. The bigoted station master Reddy refuses to pay them for ‘unfinished work’. Without money for medical treatment, Kaavanna dies on the way home. A week later, a local newspaper reports the tragic death of a young boy as he slips on fecal matter while crossing the railway tracks. It is station master Reddy’s son.

“Mad woman in the cellar”: Malathi is a destitute woman whose homelessness makes her the target of constant abuse. An ivory comb, a gift from her grandmother, comforts her, as do daily visits with her leper friend to a mansion where the owners give them food. Today is a red-letter day for her – the owners give her a red sari. Malathi ecstatically wraps it around her emaciated body, sticks the ivory comb in her ragged hair, and proudly walks down Bandilanka’s main street. She doesn’t hear the suburban bus as it crashes into her. The comb flies through the air, and the leper catches it with both his stumped hands.

“A child goes missing”: Nine-year-old Mumtaz is kidnapped from Bandilanka and taken to Mumbai. Mother Tajwar lives in hope, despite the cruel indifference of police inspector Naidu. It is Eid al-Fitr, and Mumtaz’s kidnapper forces her to wear a burka, cradle a baby, and stand in front of a mosque. A Muslim social worker who is about to enter the mosque notices and rescues her, at the same time alerting the police. They bust a national beggar ring.

“Vegetable vendor Sundari”: Street vendor Sundari pushes a vegetable cart across the rough surface of Bandilanka’s roads. Most of her customers greet her with indifference, insults, or even violence, with the exception of one house. Sheila, the mistress of the house, greets Sundari with an alphabet book. That night, Sundari opens the book, traces the outline of the letter A, places the book under her pillow, and goes to sleep dreaming of a more promising future.

“Widowhood across generations”:

1) “A husband of sixty-five years” describes how the death of a husband erases the identity of his wife.

2) “A widow reborn” has a parent challenging tradition by keeping his young widowed daughter from her narrow-minded in-laws and educating her.

3) “The fate of a child widow” tells the story of five-year-old Sundari whose 15-year-old husband dies from a snake bite. She cannot understand why she has to remove her jewelry and wear only white. Her mother refuses to destroy Sundari’s life and smuggles her out of India. The story fast-forwards to Sundari’s graduation at a college in Canada.

4) “The wonder-widow” is Venkamma, a feisty grandmother whose widowhood has not diminished her ability to confront the world. When she catches watchman Raamayya trying to steal jewelry, Venkamma grins at her own ability to outwit the thief: she has hidden the jewelry behind a bamboo fan – the least likely hiding place!

“The matter of trans lives”: The story begins in the year 2020, when a grandmother invites the local Hijras to bless her newly-born grandchild. She is still mourning the loss of her child in 1975. She remembers him being severely beaten by the boys in the village, and the broken nose that always bled at times of stress. She is about to greet the Hijras when she hears a commotion outside the house. One of the Hijras is lying on the ground, blood trickling out of her nose.

- Character Sketches?

The washerman: Tsaakali Raavanna is in his seventies – scrawny. He sports a luxuriant greying moustache and a turban. Cancer is ravaging his body, his breathing is labored. At times, he spits blood into his dhoti. His skin is a leathery brown. The sandals on his feet are frayed.

Sundari, the child bride: We see two versions of five-year-old Sundari: the child-bride and the child-widow. As a bride, she can be shown as wearing a heavy wedding sari with a gold border, gold bangles, silver anklets, a large-size bottu (bindi) on her forehead, and her plaited black braids decorated with jasmine flowers and roses. Her large black eyes are accentuated with kohl, and her hands and feet are stained with turmeric paste. The widow-version shows her stripped of all this finery, and clad in a white sari. Her face is streaked with tears, her nose is running. She doesn’t understand what is happening around her, why she can’t go outside and play with her friends.

Sarasvati Amma, the abusive mistress in “A cleaning woman’s tale”: She is clad in a traditional South-Indian Kollegal silk sari. Jewelry: diamond earrings, a heavy gold necklace, and multiple gold bangles. She has an extra-large red bottu on her forehead, painted finger- and toe-nails, silver rings on both her middle toes.

Govindan Naidu, the cruelly indifferent inspector in “A child goes missing”: he is a short man (about 5 feet 4 inches) with a paunch; instead of a uniform, he sports extravagant waistcoats much like Prime Minister Modi, and a Gandhi cap. He has a moustache that he carefully dyes pitch black. His lips are red, colored by the betel juice from the paan that he spits on the walls of his office. He always has a lit cigarette, preferably a Pall-mall, dangling from his mouth.

Sundari, the vegetable vendor in “Vegetable vendor Sundari”: She is in her late thirties, slightly built, with long black hair that she coils into a bun. She looks at least ten years older. Being all day in the sun has weathered her skin – deep wrinkles cover her face, her hands are scarred with the heavy labor of carrying loads of vegetables, pushing a cart-load of vegetables through the entire village of Bandilanka, and scrubbing the mud floor of her hut. Her sari has seen better days – the red border of the once bright green sari is frayed. Her soles of her sandals have holes.

Ramalingam, the immigrant in “Familial slaves”: he is a man in his fifties, with a daughter of marriageable age. A lifetime of working in sugar-cane fields has ruined his health. His once tall frame (5 feet 10 inches – tall for an Indian of that generation) is bent with the strain. His hands are calloused, hair and eyebrows prematurely grey. A grey stubble covers his face. His dark brown eyes with unusually long lashes look pathetically at the world.

Raasamma, the cleaning woman: she is about 5 feet 3 inches tall. The pleats of her Guntur cotton sari are tucked into the waist-band so that she can move freely as she sweeps and mops and scrubs. She has recently given birth, and the front of her sari is a little wet from breast milk. Her shiny black hair is extremely curly – she has a hard time oiling and containing it in a tight braid. Her jet-black skin is flawless. Her heels are cracked from constant exposure to cement floors and water. She wears a pair of thin copper bangles on her arms. Thick pattilu (anklets) are the only inheritance from her mother, something that she jealously guards.

- Character breakdown?

Tsaakali Raavanna (“A washerman’s dream”): is a man of strong principles and unshakeable faith. His strength of purpose comes from his absolute faith in the sanctity of his profession. He comes from a long line of washermen, a vocation that they had practiced with pride. But people called them “donkey’s load bearers.” A book about Dhobipa, the wise washerman who became one of the eighty-four mahasiddhas of ancient India, accompanies him everywhere. It has returned to him in his dreams, given him strength when floods destroyed his hut. Unusual is the strength of his love for wife Kondamma, a love that has also pulled him through many a crisis. He never fails to tell his children that they are the ones who keep Bandilanka clean. Not the priests, not the landlords, but the washermen and -women. His love extends to the animal kingdom – without his faithful bullocks Suri and Shiva, he would have collapsed even more quickly. His one addiction – smoking – is now destroying his lungs, his life. In the semi-conscious state into which he drops with increasing frequency, he relives his life with his beloved wife. These dreams are filled, not with nostalgia, but with renewed hope for a better future. Raavanna’s optimism lights up this tale.

Sundari (“The fate of a child widow”): One broad stroke of the paintbrush: innocence. This five-year-old child fills her world with colors and friends, toys and games, love and hugs. What goes through the mind of a child when she is about to be married and robbed of her childhood? She would gladly rid herself of the heavy wedding sari and jewelry, and run out to play with her friends. But when the adults strip her of these, she is terrified of a world that has suddenly gone white. Hers is a mosaic of anxiety, curiosity, and innocence.

Sarasvati Amma (“A cleaning woman’s tale”) . She exemplifies the worst features of a rich landowner’s wife in many a South-Indian village: overbearing, rapacious, exploiting culturally inflicted divides of caste and gender. She fawns on her morally corrupt brother because he is from the city, a place that symbolizes immense wealth for her. She accuses her cleaning woman of seduction, because – according to her – all lower caste women are over-sexed and whores. Money rules her world, as it does her excessive devotion to the pantheon of Hindu gods. If she prays often enough, she will be rewarded with bags of gold!

Govindan Naidu (“A child goes missing”). He is the typical officious bureaucrat, filled with self-importance, fawning on his superiors, brutal towards inferiors and those who cannot defend themselves. His islamophobia resembles that of the Vishva Hindu Parishad (Universal Hindu Council). He sees the burqa as a stain on Hindu virtue. He deliberately rejects a police uniform, choosing instead what he sees as an authentic Hindu man’s clothes: waistcoat, Gandhi cap, pancha. His remark about his six daughters bankrupting him also shows him to be misogynist.

Sundari (“Vegetable vendor Sundari”). She is ashamed of having to push her cart through the roads of Bandilanka, saddened that her husband’s work as an agricultural laborer cannot sustain them, and embarrassed about her illiteracy. Her daily rounds have sharpened her powers of observation. She sees the good, the bad, and the ugly in the homes that she sees. The fact that she accepts an alphabet book from one of her customers reveals her desire to better her prospects in life, however dismal these might be. When she slips the book under her pillow, she reveals a boldness of purpose that refuses to be diminished.

Ramalingam (“Familial slaves”): he has a perennial look of despair on his face. Crop failures, poverty, his inability to sustain his family – all these failures are deeply etched in his face. He is a middle-aged man with no future, and consequently very vulnerable to duplicity. His unshakeable belief in family loyalty and integrity renders him deaf to his wife Parvati’s skepticism. One has to visualize the gradual change in his demeanor from hope to utter despair as he is dragged into the ugly underbelly of forced labor and sex trafficking.

Raasamma (“A cleaning woman’s tale”): She is not unlike the housekeeper Aibileen in “The Help.” A drunken husband, a suckling child, and ruthless employers: these might crush her body, but not her spirit. She survives all these travails by steadfastly believing in the power of the village goddess Nookalamma to protect her and hers. Such faith is shared by the rest of her community and helps tolerate and perhaps even battle the stigma of inferiority and worthlessness imposed on them.

Posted in Uncategorized

“Bandilanka’s Forgotten Lives”

Do read the full transcript of a virtual interview that Mitrandir Journeys conducted with me about my “Bandilanka’s Forgotten Lives” (mitrandirjourneys.com/map-a-book-epi…)

#GoPlacesCreateStories

#MitrandirJourneys

Posted in Uncategorized

Bandilanka’s Forgotten Lives

Bandilanka, a fictional village in Southern India, personifies those villages across the Indian

subcontinent that are caught up in destructive customs and superstitions, and the abuse of “tradition.” My stories are a microcosm not only of India, but of the world!

What is the genesis of this collection of short stories? I pictured the many summers I spent as a child

in my maternal grandparents’ home in a remote village in the Indian state of Andhra Pradesh.

What did I remember? Whom did I remember? My Brahmin grandfather remained remote in his ‘puja’ room, and I was cocooned by an overworked grandmother, and a bevy of aunts and female cousins. As a girl, I was also subjected to practices that were accepted as traditional, and remained unchallenged despite their harmful effects. But what of those who were at the periphery of my childhood memory, those who slaved for us, and starved, and slipped through the cracks? What about their voices?

Re-reading R.K. Narayan’s “Malgudi Days” inspired me to write my own collection of stories about a fictional village called Bandilanka. “Bandilanka’s Forgotten Lives” makes those forgotten lives visible again, allows them to voice their concerns.

My stories will hopefully attract those of you who are not only interested in learning about other cultures, but also willing to critique their own. As I said, the characters in Bandilanka’s Forgotten Lives suffer from some form of injustice or loss because of the social group to which they belong: widows, washer-men and -women, night-soil workers, vegetable vendors, child laborers, domestic workers, and the LGBTQ+ community.

The stories highlight the inherent worth and dignity of the lives of these disenfranchised groups, thus challenging socially constructed divides and inequalities of caste, religion, gender, sexual orientation, and age.

I’d love to give you, my captive audience, a brief glimpse into the stories. Do go to YouTube to hear me tell you about “A widow reborn,” a story that my paternal aunt Lalitha inspired. She was widowed at the young age of 18, left with a baby daughter. But instead of wearing a widow’s garb (white in India) and being banished to the backwaters of the household, she was sent by her loving parents for further schooling! She graduated in 1943 as the first woman electrical engineer in India!

Posted in Uncategorized

My indomitable sleuths Leela and Meena

They have done it again, my courageous sleuths! The two cousins have been approached for purposes of dramatisation! Just imagine being able to see the two seventy+ Asian women appearing on Netflix! Well – cross your fingers and toes! They are unstoppable!

And now they appear again in “Murders in the Ivory Tower”!!! Just published by Pegasus in Great Britain. Here is a link to the book:

https://pegasuspublishers.com/books/kamakshi-murti/murders-in-the-ivory-tower

Posted in Uncategorized

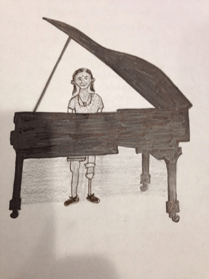

“Lalli’s Window”

Lalli, our indomitable eleven-year-old, never allows anything to stop her from trying something new and exciting! What if her left leg is a prosthetic, what if she can’t run like others in the school? She can play the piano, and she does that with passion! Good for you, Lalli, good for you!

When Lalli the piano did play

Such talent the gal did display

Her fingers would bound

O’er the keys’ wondrous sound.

Beethoven did hold such a sway!

Posted in Uncategorized

More about “Bandilanka’s Forgotten Lives”!

These forgotten people in my collection – they experience joy and pain. And they have NAMES, IDENTITIES!

The cleaning woman whose name remains unknown, whose shadow does not fall on her employers: her name is Raasamma. We buy vegetables from a vendor, but never address her by name: Sundari. And those widows, young and old, who await death on the banks of the Ganges? They had names once upon a time, they had lives that society now denies them. When we complain about clogged toilets, we don’t notice th Kaavanna and Kondamma who are condemned to removing night soil. And list goes on and on – so many lives discredited and dishonored. I just want to make them visible so that they may regain their dignity, so that my readers may challenge these socially constructed divides!

Posted in Uncategorized

Recent Comments